In 2001, the actor Matt Bomer took a role in “Guiding Light.” He had resisted it at first. A graduate of Carnegie Mellon University’s vaunted musical theater program, he felt that a soap opera was beneath him. But a few theater jobs hadn’t gone anywhere, and he had recently lost a bellman gig at a midtown hotel, so when the chance came up to play Ben Reade, a trust fund baby turned sex worker, he signed on.

Bomer had been afraid of being on camera. “I was terrified of anybody seeing that close to my soul,” he said. On the soap, he learned to say his lines, hit his marks, make a choice and stick to it. The camera left his soul alone.

In 2002, he asked the producers to write him off. He had been told that he was the director’s choice for a major new superhero movie. Then, he believes, the movie’s producers discovered that he was gay. That movie was never made.

Bomer has never been sure if that’s why the project fell apart. Like marriages and dishwashers, movies in preproduction have many ways to fail. Still, he took from the experience a painful lesson. He couldn’t be himself and have the career he wanted. Around the same time, a producer (Bomer didn’t name him) told him that if he came out publicly, he would never play leads.

It took 20 years, but Bomer, 46, has proved that producer wrong. He can currently be seen in two major projects: the Netflix film “Maestro,” which came to Netflix on Wednesday, and the Showtime romantic drama “Fellow Travelers,” set during and after the Lavender Scare of the 1950s, in which gay men and women were denied and purged from government jobs.

In the series, which concluded last week, Bomer plays Hawkins Fuller, a state department operative with a promising career, a loving wife and a passionate entanglement with a man, played by Jonathan Bailey (“Bridgerton”). Driven, magnetic, emotionally opaque, Fuller — Hawk to his intimates — has all the signifiers of a prestige drama antihero. His is a leading role. Bomer, playing him, is a leading man.

“Before this I was like, why can’t we have our Don Draper? Why can’t we have our Walter White?” Bomer said. “I don’t think I could have done it if I hadn’t worked on all the projects leading up to it.”

Bomer grew up in Spring, Tex., a suburb of Houston. His family went to church several times a week, and that church considered homosexuality an abomination, so Bomer spent much of his childhood and adolescence running from himself. In high school, he participated in forensics, football, student council, Latin Club. “Anything that kept me busy,” he said. He also acted, landing his first professional job at 18. In theater, inside the skin of a character, he felt free.

He began to date men in college, during a year abroad in Ireland. A decade into his career, once he had recurred on several series, co-starred in a Jodie Foster movie (“Flightplan”) and was firmly ensconced as the breezy lead of the USA cop-and-con-man procedural “White Collar,” he came out while receiving a humanitarian award, in 2012. He was already married then, to the publicist Simon Halls, and the father of three young boys.

Bomer isn’t sure that it was an ideal time to come out. “White Collar” was still airing, and the first “Magic Mike” film, in which he plays one of the exotic dancers, would soon premiere. But he was tired of running. And he was happy.

“I just thought, I don’t want to hide this,” he recalled on a recent morning. “Love is more important to me than anything that being my true self cost me.”

Sign up for the Watching newsletter, for Times subscribers only. Streaming TV and movie recommendations from critic Margaret Lyons and friends. Try the Watching newsletter for 4 weeks.

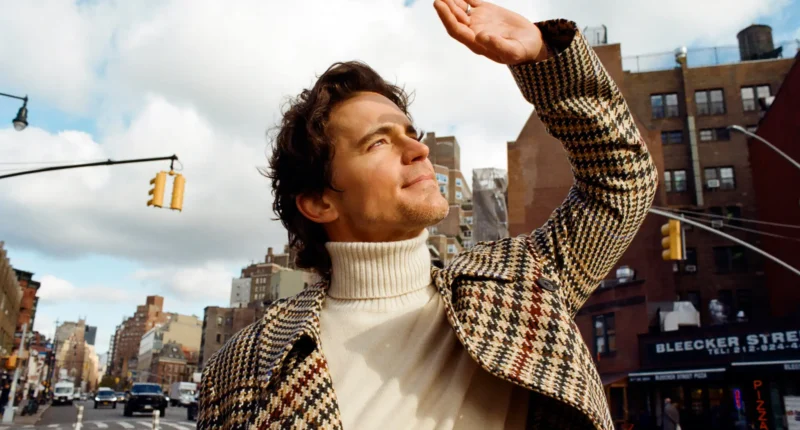

We had met an hour earlier in the middle of a West Village street. The plan had been to walk around the neighborhood, Bomer’s favorite in the city. (Although he is based in Los Angeles, he and Halls have an apartment nearby.) But it was near freezing, so after a few moments we ducked into the glassed-in back room of a pastry shop on Bleecker Street.

I can confirm that if you are a person who enjoys the company of handsome men, it is very nice to sip herbal tea across the table from Bomer. He has dark hair, light eyes, a jaw so square it could be used for geometry tutorials. Wrap that up in an off-white turtleneck sweater, and it’s heartthrob city. I had mentioned to a few friends that I would be meeting him, and they all wanted me to ask the same question: How does it feel to be that handsome?

Bomer doesn’t discount his looks, but he has the decency to be mildly embarrassed by them. “We were raised in my home to always be very humble and to not be worldly in that regard,” he said. “Having said that, I make sure to moisturize.” He favors writers and directors who see him as more than a pretty face and sculpted abs. And there is more: impishness, candor, a sense of wounds long healed.

“There’s a real sort of confident vulnerability about Matt,” said Bailey, his “Fellow Travelers” co-star.

Coming out altered Bomer’s professional trajectory, though it didn’t necessarily diminish it. “I mean, there are certain rooms that I haven’t been in since,” he said. “But I think my career became so much richer.”

As “White Collar” wound down, he took on several gay roles. He appeared in Dustin Lance Black’s “8,” a play about the overturning of the amendment banning same-sex marriage in California. He followed that with turns in Ryan Murphy’s film adaptations of “The Normal Heart” and “The Boys in the Band,” both seminal works of gay theater.

In casting Bomer in “The Normal Heart,” Murphy recalled thinking: “Maybe this is the role that can show the world what Matt can do. I remember saying to him, ‘I can tell you can do this because you have a lot to prove.’” He also perceived that Bomer, an actor who had always relied on technique and charm, who had seen performance as one more way to hide, had a deep emotional well to draw from.

“He knows what it’s like to struggle, and he knows what it’s like to be afraid, and he knows what it’s like to have people not believe in you,” Murphy said.

Even as he played these gay roles, he continued on with straight ones, building a résumé that would not have been available to an out actor even a decade before. Murphy cast him opposite Lady Gaga in a season of “American Horror Story,” and he appeared as a Hollywood producer in a miniseries version of “The Last Tycoon.” He also filmed a second “Magic Mike” movie.

Three and a half years ago, he read “Fellow Travelers,” the Thomas Mallon novel on which the series is based, with an eye toward starring in the adaptation. He was interested, but he didn’t really expect it to go forward. “There was a central part of me that has been in the business since I was 18, thinking, ‘Are the gatekeepers really going to give this the budget that it needs?’” he recalled.

But the gatekeepers did. Ron Nyswaner, the showrunner of the series, wanted Bomer for the lead, intuiting that he could play both what Hawk shows to the world (charisma, ambition) and what he conceals (heart, desire, anguish).

“Matt, for all his physical attractiveness and charm, he understands emotional pain,” Nyswaner said.

When I asked Bomer what of himself he had given to Hawk, in terms of both effort and personal experience, his answer was simple: “Everything.” Finally, he is letting the camera see into his soul. In most scenes, Bomer plays two or three emotions simultaneously, some across the surface of his face and others roiling underneath. The show includes several unusually intimate sex scenes, and Bomer gave himself to these, too. With the consent of his co-star and an intimacy coordinator, he even improvised a few unscripted moments, as when Hawk licks a lover’s armpit.

“I feel like I’ve been watching straight people express their sexuality in front of me my entire life,” Bomer said. “Now you can watch some of our experience onscreen.”

If Bomer has his way, there will be more to watch. He appears in Bradley Cooper’s “Maestro,” as the clarinetist and producer David Oppenheim, a colleague and lover of Leonard Bernstein’s. And there are plans for other series: a queer espionage drama, an adaptation of another novel. (His dream project is a “Murder She Wrote” reboot.) Then of course there are his other roles: husband, father, son, brother, advocate and activist for human rights.

Bailey, who is a decade younger, described him as “a blinding light — a good blinding light! — of energy and commitment.” Bomer was someone he had looked to as he navigated his own career, a man who had nudged open a door and kept it open for others who came after. “He’s a beacon,” Bailey said.

Predictably, Bomer takes a humbler approach. His concern is for what he has received, not what he might provide. His life has taken him, he said, from an industry suspicious of queer storytelling to one more receptive. From running from himself to settling down with a family and faith rooted in love and acceptance. Another man might discount the earlier years — the division, the prejudice, the pain — but Bomer doesn’t. It has made him who he is: a leading man and a man now able to take the lead in his own life.

“I’m grateful, ultimately, that I got to see both sides,” he said.