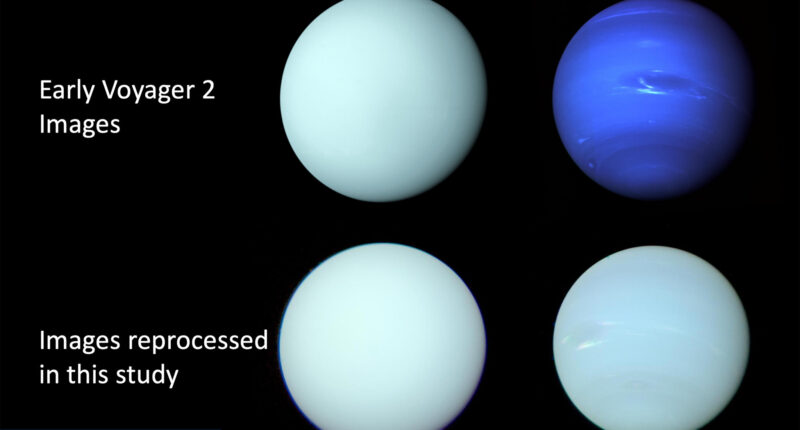

Think of Uranus and Neptune, the solar system’s outermost planets, and you may picture two distinct hues: pale turquoise and cobalt blue. But astronomers say that the true colors of these distant ice giants are more similar than their popular depictions.

Neptune is a touch bluer than Uranus, but the difference in shade is not nearly as great as it appears in common images, according to a study published on Friday in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

The results help to “set the record straight,” said Leigh Fletcher, a professor of planetary science at the University of Leicester in England and an author of the study. “There is a subtle difference in the blue shade between Uranus and Neptune, but subtle is the operative word there.”

The deep blue attributed to Neptune dates back to an artificial enhancement in the 1980s, when NASA’s Voyager 2 became the first (and still the only) spacecraft to visit the two planets.

Scientists at that time cranked up the blue in images of Neptune made by Voyager’s cameras to highlight the planet’s many curiosities, such as its south polar wave and dark spots. But as many sky watchers have known for decades, both Neptune and Uranus appear pale greenish-blue to the human eye.

“Uranus, as seen by Voyager, was pretty bland, so they made it as near to true color as we can,” said Patrick Irwin, a professor of planetary physics at the University of Oxford and an author of the study. “But with Neptune, there’s all sorts of weird things,” he said, that “get a bit washed out” with proper color correction.

Enhanced images of Neptune often include captions that address the artificial color, but the vision of a deep blue planet has endured.

Dr. Irwin and his colleagues used advanced instruments on the Hubble Space Telescope and on the Very Large Telescope in Chile to resolve the colors of the planets as accurately as possible.

They also reviewed an immense observational record of both planets captured by Lowell Observatory in Arizona between 1950 and 2016.

The results confirm that Uranus is only slightly paler than Neptune, because of the thicker layer of aerosol haze that lightens its color.

The Lowell data set also shed new light on the mysterious color shifts that Uranus experiences over its extreme seasons.

For years, astronomers have puzzled over why Uranus is tinted green during its solstices but radiates a bluer glow at its equinoxes. The pattern is linked to Uranus’s odd position — tilted almost entirely on its side. Over the course of an 84-year orbit around the sun, Uranus’s poles are plunged into decades of perpetual light or darkness in the summers and winters, while the equatorial regions face the sun near the equinoxes.

Uranus’s shifting colors can be partly explained by atmospheric methane. Because methane absorbs red and green light, the equator ends up reflecting more blue light; by contrast, the poles, which have half as much methane, are tinted slightly green. The new study confirms this dynamic, and shows that a “hood” of ice particles coalesces over the sunlit poles of Uranian summer, boosting the greening effect.

The study “opens the door to many future studies aiming at understanding Uranus’s atmosphere and its seasons,” said Ravit Helled, a professor of theoretical astrophysics at the University of Zurich who was not involved in the research. This work, she added, can “improve our understanding of the internal structure and thermal evolution of the planet.”

For Heidi Hammel, an astronomer who worked on Voyager’s imaging team in 1989, the new study is the latest chapter in a longstanding quest to bring the planet’s real color to light.

“For the public, I hope that this paper can help undo the decades of misinformation about Neptune’s color,” said Dr. Hammel, who now serves as vice president for science at the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy. “Strike the word ‘azure’ from your vocabulary when discussing Neptune!”

The gap between the public perception and the reality of Neptune illustrates just one of the many ways data is manipulated to emphasize certain features or enhance the appeal of astronomical visualizations. For instance, the stunning images released from the James Webb Space Telescope are composite false-color versions of the original infrared observations.

“There’s never been an attempt to deceive,” Dr. Fletcher said, “but there has been an attempt to tell a story with these images by making them aesthetically pleasing to the eye so that people can enjoy these beautiful scenes in a way that is, maybe, more meaningful than a fuzzy, gray, amorphous blob in the distance.”